Der Todeszug is a project that envisioned using an entire train as a canvas. Not as a bombed out suburban train, but a civic connection between the seperated Belgrade and Sarajevo, whose train connection was severed for over 18 years due to war and nation

Europe’s Unfinished Trains of Murder: The LGB Group’s Der Todeszug By Christophe Bachalard

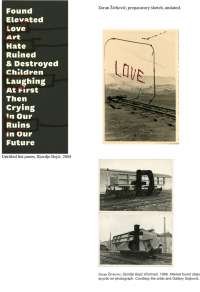

I first I heard about the work of The LGB Group thanks to the book To Warmann by Djordje Bojić, itself a kind of sad, unrealized (or at least unfinished) autobiography. And when I looked further it was the text-based, iconic works that I was attracted to, the endless games and original use of text in art made me, as a fan of typography, graphic design but also politics and the engaged act, an instant fan and advocate. The use of text in so much LGB art, whether it be in French, Serbian, English or German, take your pick, in either Cyrillic or Latin, was always attractive, it caught my eye, made me stop and think. The first time I saw the work of The LGB Group in person it was as we say in France, ‘un coup de foudre’: LOVE BLACKS GAYS CROWS by Bojić was a masterful effacement of Jorg Haider at a time when the fascist was doing very well politically in Austria. In a similar vein, Der Todeszug was a project that looked at Europe’s more troubling contemporary and its relation to its fascist, totalitarian past. Bojić first came up with it when he wanted to travel from Belgrade to Sarajevo in 2004 and realised that no train had been running between the two cities for a decade. This was once a rather glamorous line, The Olympic Express, with young attractive stewards and plush fittings, but obviously with the wars of 1990s it was out of use, new national borders in place and infrastructure blown to pieces. Always looking for new ways to express his disembodied poems, Bojić thought of Tito’s final journey through Yugoslavia, when the train carrying the dead leader was seen and saluted by thousands of mourners, a spectacle of lasting significance for the young artist. It would be simple: his ‘list’ poems married with other LGB artists’ work across the wagons of a train that The LGB Group would somehow manage to get put in place, despite all the animosity and division separating Belgrade and Sarajevo. Zoran Živkovic was of course The LGB Group’s train artist par excellence, he had been obsessed with borders, border crossings and espionage ever since he read Jean Genet’s Diary of a Thief at the same time his extended family were sent into exile thanks to the war in Kosovo. In autumn 2004 Bojić was very excited about his new idea, something that would be monumental – he always wanted to find a way into the monumental, to blow his words up to epic dimensions, be bigger than Weiner, bigger than advertising, bigger than, ultimately, anything he would ever produce himself – and this would be his way of being so and of contributing to the peace that was slowly forming. He returned to his adopted Paris and immediately started to draw up proposals and sent Živkovic his initial ideas, asking him to respond with proofs for them to send to the powers involved. They had a fruitful exchange, a very LGB affair, letters and emails and phonecalls from Paris to Belgrade and back again. But, sadly, the bureaucracy extent in the region would be the project’s undoing. Despite the group’s enthusiasm and the work of the artists and their concerted efforts to persuade the Serbian and Bosnian authorities to open up the route to a train bedecked in Bojician poetry, the project finally was put to the wayside. Its grandiose vision too much too soon for a region still picking up the pieces. Five years later, just a month after Bojić’s dead body was pulled from the Seine, and 18 years of non-existence, the first rickety train left Belgrade to Sarajevo. But without much poetry to speak of.

First published in The Kakofonie – A European Journal of Art and Literature Translated by John Holten

Der Todeszug is a project that envisioned using an entire train as a canvas. Not as a bombed out suburban train, but a civic connection between the seperated Belgrade and Sarajevo, whose train connection was severed for over 18 years due to war and nation

Europe’s Unfinished Trains of Murder: The LGB Group’s Der Todeszug By Christophe Bachalard

I first I heard about the work of The LGB Group thanks to the book To Warmann by Djordje Bojić, itself a kind of sad, unrealized (or at least unfinished) autobiography. And when I looked further it was the text-based, iconic works that I was attracted to, the endless games and original use of text in art made me, as a fan of typography, graphic design but also politics and the engaged act, an instant fan and advocate. The use of text in so much LGB art, whether it be in French, Serbian, English or German, take your pick, in either Cyrillic or Latin, was always attractive, it caught my eye, made me stop and think. The first time I saw the work of The LGB Group in person it was as we say in France, ‘un coup de foudre’: LOVE BLACKS GAYS CROWS by Bojić was a masterful effacement of Jorg Haider at a time when the fascist was doing very well politically in Austria. In a similar vein, Der Todeszug was a project that looked at Europe’s more troubling contemporary and its relation to its fascist, totalitarian past. Bojić first came up with it when he wanted to travel from Belgrade to Sarajevo in 2004 and realised that no train had been running between the two cities for a decade. This was once a rather glamorous line, The Olympic Express, with young attractive stewards and plush fittings, but obviously with the wars of 1990s it was out of use, new national borders in place and infrastructure blown to pieces. Always looking for new ways to express his disembodied poems, Bojić thought of Tito’s final journey through Yugoslavia, when the train carrying the dead leader was seen and saluted by thousands of mourners, a spectacle of lasting significance for the young artist. It would be simple: his ‘list’ poems married with other LGB artists’ work across the wagons of a train that The LGB Group would somehow manage to get put in place, despite all the animosity and division separating Belgrade and Sarajevo. Zoran Živkovic was of course The LGB Group’s train artist par excellence, he had been obsessed with borders, border crossings and espionage ever since he read Jean Genet’s Diary of a Thief at the same time his extended family were sent into exile thanks to the war in Kosovo. In autumn 2004 Bojić was very excited about his new idea, something that would be monumental – he always wanted to find a way into the monumental, to blow his words up to epic dimensions, be bigger than Weiner, bigger than advertising, bigger than, ultimately, anything he would ever produce himself – and this would be his way of being so and of contributing to the peace that was slowly forming. He returned to his adopted Paris and immediately started to draw up proposals and sent Živkovic his initial ideas, asking him to respond with proofs for them to send to the powers involved. They had a fruitful exchange, a very LGB affair, letters and emails and phonecalls from Paris to Belgrade and back again. But, sadly, the bureaucracy extent in the region would be the project’s undoing. Despite the group’s enthusiasm and the work of the artists and their concerted efforts to persuade the Serbian and Bosnian authorities to open up the route to a train bedecked in Bojician poetry, the project finally was put to the wayside. Its grandiose vision too much too soon for a region still picking up the pieces. Five years later, just a month after Bojić’s dead body was pulled from the Seine, and 18 years of non-existence, the first rickety train left Belgrade to Sarajevo. But without much poetry to speak of.

First published in The Kakofonie – A European Journal of Art and Literature Translated by John Holten