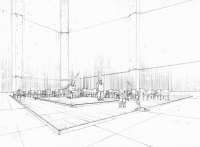

Third Act for Goya is the unrealized component of Daniel Joseph Martinez’ android trilogy. Based on the central figure in Francisco Goya’s The Inquisition Scene (c.1816), the mechanical doppelganger of the artist gets up, steps to the edge of the platform, and pukes on the floor, creating a growing pile of abject vomit. It follows the two earlier episodes where animatronics doppelgangers allegorically assumed real or fictional characters. The first, To Make a Blind Man Murder for the Things He’s Seen (Happiness Is Overrated) (2002), references Yukio Mishima’s seppuku ritual suicide as the figure repeatedly attempts to cut its wrists but fails and breaks into a crackling laughter. The question of the cyborg’s agency in relation to its own death is also probed in the second work from the trilogy Call Me Ishmael or The Fully Enlightened Earth Radiates Disaster Triumphant (2006, recreated in 2008) where the figure’s repetitive series of convulsions are rendered after Daryl Hannah’s swansong in Blade Runner. As in the larger project of science fiction, the trilogy aims to understand what is human by pushing the boundaries of what is considered human. The radical figuration of the artwork and its spectacular behavior elicit a new kind of relation between viewer and work. Not sculpture, not installation, not performance, not film, (the relationship to the object is not mediated enough for suspension of disbelief), the viewing experience in all three cases elicits historical frameworks such as the scaffolding, freak-show, or ethnographic spectacle, but with a contemporary demand for viewer awareness and self-reflection. In all three cases this is achieved through the architecture of the installation that foreground the room, platform, or stage, such that the audience must become aware of the act of viewing itself. The third component is critical for completing the cycle of references accumulated in these works. Cutting across genres and literary paradigms, they disrupt our philosophical definition of being by measuring our current understanding of existence against the projected possibilities of the future.

Third Act for Goya is the unrealized component of Daniel Joseph Martinez’ android trilogy. Based on the central figure in Francisco Goya’s The Inquisition Scene (c.1816), the mechanical doppelganger of the artist gets up, steps to the edge of the platform, and pukes on the floor, creating a growing pile of abject vomit. It follows the two earlier episodes where animatronics doppelgangers allegorically assumed real or fictional characters. The first, To Make a Blind Man Murder for the Things He’s Seen (Happiness Is Overrated) (2002), references Yukio Mishima’s seppuku ritual suicide as the figure repeatedly attempts to cut its wrists but fails and breaks into a crackling laughter. The question of the cyborg’s agency in relation to its own death is also probed in the second work from the trilogy Call Me Ishmael or The Fully Enlightened Earth Radiates Disaster Triumphant (2006, recreated in 2008) where the figure’s repetitive series of convulsions are rendered after Daryl Hannah’s swansong in Blade Runner. As in the larger project of science fiction, the trilogy aims to understand what is human by pushing the boundaries of what is considered human. The radical figuration of the artwork and its spectacular behavior elicit a new kind of relation between viewer and work. Not sculpture, not installation, not performance, not film, (the relationship to the object is not mediated enough for suspension of disbelief), the viewing experience in all three cases elicits historical frameworks such as the scaffolding, freak-show, or ethnographic spectacle, but with a contemporary demand for viewer awareness and self-reflection. In all three cases this is achieved through the architecture of the installation that foreground the room, platform, or stage, such that the audience must become aware of the act of viewing itself. The third component is critical for completing the cycle of references accumulated in these works. Cutting across genres and literary paradigms, they disrupt our philosophical definition of being by measuring our current understanding of existence against the projected possibilities of the future.