Unrealized Project Title: Found Object: Robert Allen Initially proposed: 1991 Artist: Antoinette LaFarge

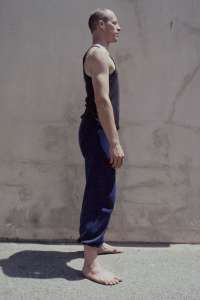

Please refer to the accompanying JPEG from the original proposal.

One day in 1991, I came across a flyer for a juried exhibition entitled “Found Object as Art” with this extremely vague call for entries:

“Open to all living artists working in assemblage of found objects. Work may be wall-hung, free-standing, or mounted on the artists’ [sic] own pedestal. We have a few pedestals if needed.”

And I started thinking about the kinds of things that typically pass as found art. Thrift-store paintings. Bird’s nests and driftwood and broken toys. Map fragments and old letters. Ancestor photos. Architectural remnants, machine parts, plastic souvenirs. Most of all, assemblages of the above. I wanted to propose something different, and I was struck by how the call typologized art as wall-hung, free-standing, or pedestal-mounted. This led to a train of thought about the metaphor of ‘putting something on a pedestal’, and about how things can be both literal and metaphorical, and about what qualifies as an object in the first place, let alone a found one.

So I sent in the following proposal, which was cryptic in part because it was required to fit on a 3×5-inch card:

"Found Object" Title: Robert Allen Medium: Biological materials Dimensions: 76″ h x 22″ w x 9″ d Price: NFS This self-assembled Found Object is well-hung, free-standing, and permanently mounted on a pedestal (the artist put this Found Object on a pedestal during their courtship; no other pedestal is required). For purposes of display, this may be treated as a Found Love Object and/or a Found Sex Object. This Found Object can easily pass through a 3′ x 6’8″ door [this was a requirement of the call for entries], either on own initiative or following a polite request.

Some weeks later my entry form came back stamped WORK NOT ACCEPTED.

Was it the tongue-in-cheek write-up that killed the proposal? Robert, who was then a dancer and choreographer, was prepared to work with me and the curator on important matters like whether Robert would need to be completely stationary, whether he would speak, and how long each day he would participate in the exhibition, since I wasn’t proposing this as an ordeal project à la Marina Abramowicz. These kinds of things should probably have been included in the original proposal, but as it happened, I was right in the midst of preparations to move from California to Germany for what turned into a stay of several years, so perhaps my hasty write-up reflected a certain ambivalence about the prospect of participating in this show at the same time.

Or did the problem lie in a mismatch between artistic and curatorial intentions? The juror for this show was a well-known artist who worked solidly within the mainstream of found art, especially the subtype that pays homage to the boxes of Joseph Cornell. I may be wronging him, but it is possible that he would have thought my living found art was too much of a stretch no matter how I phrased my proposal.

Flash forward 20 years. I am proposing this piece for the Agency of Unrealized Projects not just because it was never realized, but more especially because it can no longer be realized in its original form. The titular Robert Allen is now two decades years older, and while he is still willing to participate in an exhibition as a Found Object, he is no longer precisely the same person shown in the proposal photograph, either physically or psychically. But this is not solely a matter of loss, either. Robert is still the love of my life, so the project in this later incarnation— which would include both the present-day Robert (in the flesh) and the past Robert (of the photograph)—bears witness to what has endured in our partnership of life and art. Even if it cannot reconstruct what is gone, it embraces the delicate contingencies that keep discovery, love, and time in perpetual tension.

Unrealized Project Title: Found Object: Robert Allen Initially proposed: 1991 Artist: Antoinette LaFarge

Please refer to the accompanying JPEG from the original proposal.

One day in 1991, I came across a flyer for a juried exhibition entitled “Found Object as Art” with this extremely vague call for entries:

“Open to all living artists working in assemblage of found objects. Work may be wall-hung, free-standing, or mounted on the artists’ [sic] own pedestal. We have a few pedestals if needed.”

And I started thinking about the kinds of things that typically pass as found art. Thrift-store paintings. Bird’s nests and driftwood and broken toys. Map fragments and old letters. Ancestor photos. Architectural remnants, machine parts, plastic souvenirs. Most of all, assemblages of the above. I wanted to propose something different, and I was struck by how the call typologized art as wall-hung, free-standing, or pedestal-mounted. This led to a train of thought about the metaphor of ‘putting something on a pedestal’, and about how things can be both literal and metaphorical, and about what qualifies as an object in the first place, let alone a found one.

So I sent in the following proposal, which was cryptic in part because it was required to fit on a 3×5-inch card:

"Found Object" Title: Robert Allen Medium: Biological materials Dimensions: 76″ h x 22″ w x 9″ d Price: NFS This self-assembled Found Object is well-hung, free-standing, and permanently mounted on a pedestal (the artist put this Found Object on a pedestal during their courtship; no other pedestal is required). For purposes of display, this may be treated as a Found Love Object and/or a Found Sex Object. This Found Object can easily pass through a 3′ x 6’8″ door [this was a requirement of the call for entries], either on own initiative or following a polite request.

Some weeks later my entry form came back stamped WORK NOT ACCEPTED.

Was it the tongue-in-cheek write-up that killed the proposal? Robert, who was then a dancer and choreographer, was prepared to work with me and the curator on important matters like whether Robert would need to be completely stationary, whether he would speak, and how long each day he would participate in the exhibition, since I wasn’t proposing this as an ordeal project à la Marina Abramowicz. These kinds of things should probably have been included in the original proposal, but as it happened, I was right in the midst of preparations to move from California to Germany for what turned into a stay of several years, so perhaps my hasty write-up reflected a certain ambivalence about the prospect of participating in this show at the same time.

Or did the problem lie in a mismatch between artistic and curatorial intentions? The juror for this show was a well-known artist who worked solidly within the mainstream of found art, especially the subtype that pays homage to the boxes of Joseph Cornell. I may be wronging him, but it is possible that he would have thought my living found art was too much of a stretch no matter how I phrased my proposal.

Flash forward 20 years. I am proposing this piece for the Agency of Unrealized Projects not just because it was never realized, but more especially because it can no longer be realized in its original form. The titular Robert Allen is now two decades years older, and while he is still willing to participate in an exhibition as a Found Object, he is no longer precisely the same person shown in the proposal photograph, either physically or psychically. But this is not solely a matter of loss, either. Robert is still the love of my life, so the project in this later incarnation— which would include both the present-day Robert (in the flesh) and the past Robert (of the photograph)—bears witness to what has endured in our partnership of life and art. Even if it cannot reconstruct what is gone, it embraces the delicate contingencies that keep discovery, love, and time in perpetual tension.