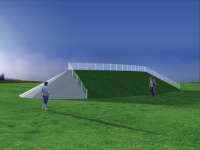

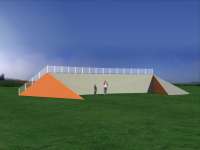

Cove Cove is a site work that would be made of earth, concrete and aluminum. The bulk of the mass is earth, which would be compacted and finished with a layer of topsoil. The curved wall, two orange vertical panels and the cone would all need to have substantial concrete footings to carry their weight, since they would be 5 ½” thick and reinforced with steel rebar. The earth mound that backs up the concrete structure would be finished with sod to minimize erosion immediately. In order to allow viewers to climb the mound, a tubular aluminum frame would be placed for safety. The piece references the North American mound-building tradition, which I had been aware of since my youth. The Nikwasi mound in Franklin, North Carolina, near where I grew up, was the first I knew, was in the heart of the Cherokee nation. In 1985, during a visit to the Orkney Islands, I visited a number of prehistoric sites, but was most taken with Maeshowe, a chambered tomb covered by a mound. Later still, when I read Charles Frazier's "Cold Mountain", his mention of William Bartram's travels through the southeast in 1775 led me to read Bartram's account. He mentions numerous mound complexes, that Native Americans told him were built by "the ancients". To the west of my current home in southern Illinois is a Native American mound complex called Cahokia. At hits zenith, the population neared 30,000. In 2003 I began work on "Lightspill", a site work for the Cedarhurst Center for the Arts Sculpture Park in Mount Vernon, Illinois. At the time I began planning Lightspill, I had visited Cahokia and decided to build a mound containing an open volume that can be entered through two tunnels. Three years later the piece was dedicated. The mound is sixteen feet high and measures 65 feet at the base. The two tunnels face southeast and southwest and are lit by the sun in early morning and late evening.

Cove Cove is a site work that would be made of earth, concrete and aluminum. The bulk of the mass is earth, which would be compacted and finished with a layer of topsoil. The curved wall, two orange vertical panels and the cone would all need to have substantial concrete footings to carry their weight, since they would be 5 ½” thick and reinforced with steel rebar. The earth mound that backs up the concrete structure would be finished with sod to minimize erosion immediately. In order to allow viewers to climb the mound, a tubular aluminum frame would be placed for safety. The piece references the North American mound-building tradition, which I had been aware of since my youth. The Nikwasi mound in Franklin, North Carolina, near where I grew up, was the first I knew, was in the heart of the Cherokee nation. In 1985, during a visit to the Orkney Islands, I visited a number of prehistoric sites, but was most taken with Maeshowe, a chambered tomb covered by a mound. Later still, when I read Charles Frazier's "Cold Mountain", his mention of William Bartram's travels through the southeast in 1775 led me to read Bartram's account. He mentions numerous mound complexes, that Native Americans told him were built by "the ancients". To the west of my current home in southern Illinois is a Native American mound complex called Cahokia. At hits zenith, the population neared 30,000. In 2003 I began work on "Lightspill", a site work for the Cedarhurst Center for the Arts Sculpture Park in Mount Vernon, Illinois. At the time I began planning Lightspill, I had visited Cahokia and decided to build a mound containing an open volume that can be entered through two tunnels. Three years later the piece was dedicated. The mound is sixteen feet high and measures 65 feet at the base. The two tunnels face southeast and southwest and are lit by the sun in early morning and late evening.