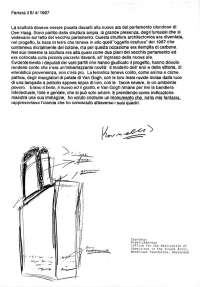

La scultura doveva essere posata davanti alla nuova ala del parlamento olandese di Den Haag. Sono partito dalla struttura ampia, di grande presenza, degll fumaioli che si vedevano sui tetto del vecchio parlamento. Questa strutture architectonica era diventata, nel progetto, la base in terro che teneva in alto quell "Oggetto sculture" del 1967 che conteneva inizialmente del contone, ma per questa occasione era riempita di carbone. Nel suo insieme la sculture era alta quasi come due piani del vecchio parlamento ed ero collocata sulla piccola piazzeta davanti, all'ingresso della nuova ala. Evidentemente I deputati dei varil partiti che hanno giudicato il progetto, hanno dovuto rendersi conto che c'era un'imbarrazzanti novità: il modello dell'eroi e della vittoria, di pathos, degli manglatori di patate di Van Gogh, con le loro mani ruvide incise dalla luce povero. Erano il bello, il nuovo ed il giusto, e Van Gogh rimane per me la bandiera intellectuale, folle e geniale, che si puó solo amare. E prendendo come indicazione maestra una sua immagine, ho voluto construire un monumento che, nella mia fantasia, rappresentava l'olanda che ho conosciuto attraverso i suoi quadri.

a note on Jannis Kounellis' Monument to Democracy. The Hague, Holland (rejected design)

Usually, when a projected Monument of national importance under discussion, the nationality of the artist is an issue. Not in this case. When the new Parliament Building in The Hague was near completion, some years ago, the Cabinet of Ministers decided to present Parliament with a public sculpture, a monument, to be erected (after consultation with the architect, Pie de Bruin) on a triangular piazza in front of the building, the Minister of Culture asked me to propose an artist. Should he or she be of Dutch nationality, I asked. It was decided that, in this era of European integration, the artist could come from any nation of the European Union. I proposed Kounellis. I did not want a decorative, abstract sculpture but a work that in its form, could embody a certain meaning. Given the symbolist nature of Kounellis' work, I decided that he would be the ideal choice. After I discussed the commission with the artist, and after he together with the architect, visited the location, Kounellis produced a wonderful and truly monumental design: a huge pedestal of steel (about 8 meters high) on which a container with coal was placed. The pedestal would carry, as inscription, the text of the first article of the Dutch Constitution, stating that everybody, of whatever race or creed, is equal before the law. Then I sent the design to the Minister of Culture, accompanied with a short letter in which I suggested possible interpretation. The coal, I wrote could refer to the Industrial Revolution and thus to the Enlightenment. In a symbolic sense, this reference implied that government is the work of men, and not the result of divine inspiration. My 'explanation' was only brief and tentative; it was not meant to be exhaustive. --- In the meantime, the committee that supervised the process of building the new Parliament asked to discuss the design. As is the custom in Holland, this committee consisted of representatives of all the 'users' of the building -- not only parliamentarians but also office staff, journalists and other groups. The design for the monument had become known and there was concern about its aesthetic character. There was also concern in particular among politicians from certain parties with a strong calvinist background, that the monument denied the presence of divine inspiration in society and in the world. As it happened, in the letter to Parliament in which she offered the monument as a special present, the Minister of Culture had, without my knowledge, quoted from my brief letter that had not been written for this purpose. The meeting of the committee of supervision was, as Kounellis observed later a very dignified affair. He had enjoyed, he said, the seriousness of the democratic process -- and he fully agreed that public projects of this nature should be discussed publicly. Before the meeting he was received by the Parliament's President who expressed his interest and who seemed to support the project. The committee asked a number of questions to which Kounellis gracefully replied. One Calvinist Member of Parliament inquired whether Kounellis considered himself a monotheist. Of course, the artist said, I was raised a Greek Orthodox. After about one hour and a half, the committee was satisfied, as fas as they were concerned, the monument could be built. Yet, by this time, the propriety of the project continued to be discussed, among politicians (not members of the Commitee of Supervision) and in the press as well. The issue of divine inspiration or not stayed alive: also people began to attack the esthetic character of the sculpture. They simply did not like it. As the Minister of Culture has offered the work to Parliament by letter, some parliamentarians required that her offer )the acceptance of it) should be discussed in Parliament (in pleno) -- also because the monument was to be financed out of the budget of the Ministry of Culture. As Parliament holds the rights of budget, it should be allowed to bote on the expense. In this point the President of the Parliament, in my view, should have refused such a discussion as the matter had been properly dealt with in the Committee of Supervision. For political reasons he had to allow the discussion. Thus the decision whether the sculpture could or could not be built, was hijacked by the 150 members of Parliament whereas it was, in the proper course of procedure, the right of the Committee (with representative of the other groups of users) to take that decision. In Parliament work, say 2000 people from secretaries to security to cleaning staff. By Parliament taking the decision in his hands, the 150 members deprived 1850 other users of their legal rights. The discussion in Parliament, then, was vulgar. The majority voted against the monument. most of them just because they disliked it. --- Many months later the new building was officially inaugurated in the presence of the Queen. During the ceremony a piece of music by a modern Greek composer was played. Many people in the hall were bored by it. When it finished one parliamentarian (who had been in favor of the monument) mumbled, but for everyone to hear: 'that was Kounellis revenge.'

Rudi Fuchs

La scultura doveva essere posata davanti alla nuova ala del parlamento olandese di Den Haag. Sono partito dalla struttura ampia, di grande presenza, degll fumaioli che si vedevano sui tetto del vecchio parlamento. Questa strutture architectonica era diventata, nel progetto, la base in terro che teneva in alto quell "Oggetto sculture" del 1967 che conteneva inizialmente del contone, ma per questa occasione era riempita di carbone. Nel suo insieme la sculture era alta quasi come due piani del vecchio parlamento ed ero collocata sulla piccola piazzeta davanti, all'ingresso della nuova ala. Evidentemente I deputati dei varil partiti che hanno giudicato il progetto, hanno dovuto rendersi conto che c'era un'imbarrazzanti novità: il modello dell'eroi e della vittoria, di pathos, degli manglatori di patate di Van Gogh, con le loro mani ruvide incise dalla luce povero. Erano il bello, il nuovo ed il giusto, e Van Gogh rimane per me la bandiera intellectuale, folle e geniale, che si puó solo amare. E prendendo come indicazione maestra una sua immagine, ho voluto construire un monumento che, nella mia fantasia, rappresentava l'olanda che ho conosciuto attraverso i suoi quadri.

a note on Jannis Kounellis' Monument to Democracy. The Hague, Holland (rejected design)

Usually, when a projected Monument of national importance under discussion, the nationality of the artist is an issue. Not in this case. When the new Parliament Building in The Hague was near completion, some years ago, the Cabinet of Ministers decided to present Parliament with a public sculpture, a monument, to be erected (after consultation with the architect, Pie de Bruin) on a triangular piazza in front of the building, the Minister of Culture asked me to propose an artist. Should he or she be of Dutch nationality, I asked. It was decided that, in this era of European integration, the artist could come from any nation of the European Union. I proposed Kounellis. I did not want a decorative, abstract sculpture but a work that in its form, could embody a certain meaning. Given the symbolist nature of Kounellis' work, I decided that he would be the ideal choice. After I discussed the commission with the artist, and after he together with the architect, visited the location, Kounellis produced a wonderful and truly monumental design: a huge pedestal of steel (about 8 meters high) on which a container with coal was placed. The pedestal would carry, as inscription, the text of the first article of the Dutch Constitution, stating that everybody, of whatever race or creed, is equal before the law. Then I sent the design to the Minister of Culture, accompanied with a short letter in which I suggested possible interpretation. The coal, I wrote could refer to the Industrial Revolution and thus to the Enlightenment. In a symbolic sense, this reference implied that government is the work of men, and not the result of divine inspiration. My 'explanation' was only brief and tentative; it was not meant to be exhaustive. --- In the meantime, the committee that supervised the process of building the new Parliament asked to discuss the design. As is the custom in Holland, this committee consisted of representatives of all the 'users' of the building -- not only parliamentarians but also office staff, journalists and other groups. The design for the monument had become known and there was concern about its aesthetic character. There was also concern in particular among politicians from certain parties with a strong calvinist background, that the monument denied the presence of divine inspiration in society and in the world. As it happened, in the letter to Parliament in which she offered the monument as a special present, the Minister of Culture had, without my knowledge, quoted from my brief letter that had not been written for this purpose. The meeting of the committee of supervision was, as Kounellis observed later a very dignified affair. He had enjoyed, he said, the seriousness of the democratic process -- and he fully agreed that public projects of this nature should be discussed publicly. Before the meeting he was received by the Parliament's President who expressed his interest and who seemed to support the project. The committee asked a number of questions to which Kounellis gracefully replied. One Calvinist Member of Parliament inquired whether Kounellis considered himself a monotheist. Of course, the artist said, I was raised a Greek Orthodox. After about one hour and a half, the committee was satisfied, as fas as they were concerned, the monument could be built. Yet, by this time, the propriety of the project continued to be discussed, among politicians (not members of the Commitee of Supervision) and in the press as well. The issue of divine inspiration or not stayed alive: also people began to attack the esthetic character of the sculpture. They simply did not like it. As the Minister of Culture has offered the work to Parliament by letter, some parliamentarians required that her offer )the acceptance of it) should be discussed in Parliament (in pleno) -- also because the monument was to be financed out of the budget of the Ministry of Culture. As Parliament holds the rights of budget, it should be allowed to bote on the expense. In this point the President of the Parliament, in my view, should have refused such a discussion as the matter had been properly dealt with in the Committee of Supervision. For political reasons he had to allow the discussion. Thus the decision whether the sculpture could or could not be built, was hijacked by the 150 members of Parliament whereas it was, in the proper course of procedure, the right of the Committee (with representative of the other groups of users) to take that decision. In Parliament work, say 2000 people from secretaries to security to cleaning staff. By Parliament taking the decision in his hands, the 150 members deprived 1850 other users of their legal rights. The discussion in Parliament, then, was vulgar. The majority voted against the monument. most of them just because they disliked it. --- Many months later the new building was officially inaugurated in the presence of the Queen. During the ceremony a piece of music by a modern Greek composer was played. Many people in the hall were bored by it. When it finished one parliamentarian (who had been in favor of the monument) mumbled, but for everyone to hear: 'that was Kounellis revenge.'

Rudi Fuchs