Irlam House is a sixteen story tower block in Bootle, Merseyside. Sometime in the late 1980’s the resident Caretaker came into possession of a substantial collection of drawings. The drawings came to our attention when he recently brought one study to the Conservation Department claiming it to be suffering from ‘vibration issues’.

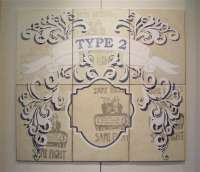

After some deliberation we have identified the works as composite templates and graphics for banner designs, of the type made popular amongst the British Labour Movement. They were retrieved from a flat on the 14th floor that had apparently been vacated without forewarning by its tenants. The Caretaker has written extensively about the works in the context of his PHD studies (titled: The telepathic turn; affective states, autonomous sociality & overcoming the bio-political.).

The occupants, by all accounts unseen throughout their tenure, had also used the accommodation as a makeshift design workshop and had secured funding through the ‘Enterprise Allowance Scheme’. Though for some unknown reason they had abandoned this venture before making any attempt to market their wares. The caretaker, whilst apparently maintaining some form of communication with the group became evasive when asked of their present whereabouts.

Aside from the works, we have an amount of information gleaned from the Caretaker that mostly recounts the group’s composition and methodology relating to their production. He professed to never having met any of them, though he thought that they probably originated from a variety of nationalities. He had a tendency to be dismissive of the works and stressed that the significance of the group’s activities should primarily be gauged by “their capacity for imagining in the midst of political struggle” and that this stemmed from “what we might term contaminating affects - arising out of a social interaction between bodies”.

He felt that the group were creating works that had no representational basis, although they were concerned with “objects emerging as part of the sensual experience of the surrounding environs”. He believed that they were immersed in experimentation, analysing craft and design aesthetics, testing the limits of authorship. Though on the face of it, their modus operandi was strangely paradoxical. It seems as though they had set up, or had proposed to activate an archetypical ‘Fordist’ assembly line dealing in specific ‘types’ of output.

Though he recognised that his own interests were for the most part tied to the realm of praxis, the caretaker joined in with a passive examination of the collection - “the residue”. During this his mood changed as he surprisingly opened up to speak about the group’s identification with ‘the occult’ and a possible engagement with paranormal phenomena. He believed that the designs were “invoked through some process of automatism” but my conjecture about the energy generated by the group possibly being locked into the works was met with bemusement.

Ultimately, he could only admit to feeling ambivalent about our proposal to exhibit the collection. He finally commented that the works “might resonate, find a frequency …maybe even enter into dialogue with the dead artists also showing therein” but that he “personally thought they’d be better off left out in the street.”

Irlam House is a sixteen story tower block in Bootle, Merseyside. Sometime in the late 1980’s the resident Caretaker came into possession of a substantial collection of drawings. The drawings came to our attention when he recently brought one study to the Conservation Department claiming it to be suffering from ‘vibration issues’.

After some deliberation we have identified the works as composite templates and graphics for banner designs, of the type made popular amongst the British Labour Movement. They were retrieved from a flat on the 14th floor that had apparently been vacated without forewarning by its tenants. The Caretaker has written extensively about the works in the context of his PHD studies (titled: The telepathic turn; affective states, autonomous sociality & overcoming the bio-political.).

The occupants, by all accounts unseen throughout their tenure, had also used the accommodation as a makeshift design workshop and had secured funding through the ‘Enterprise Allowance Scheme’. Though for some unknown reason they had abandoned this venture before making any attempt to market their wares. The caretaker, whilst apparently maintaining some form of communication with the group became evasive when asked of their present whereabouts.

Aside from the works, we have an amount of information gleaned from the Caretaker that mostly recounts the group’s composition and methodology relating to their production. He professed to never having met any of them, though he thought that they probably originated from a variety of nationalities. He had a tendency to be dismissive of the works and stressed that the significance of the group’s activities should primarily be gauged by “their capacity for imagining in the midst of political struggle” and that this stemmed from “what we might term contaminating affects - arising out of a social interaction between bodies”.

He felt that the group were creating works that had no representational basis, although they were concerned with “objects emerging as part of the sensual experience of the surrounding environs”. He believed that they were immersed in experimentation, analysing craft and design aesthetics, testing the limits of authorship. Though on the face of it, their modus operandi was strangely paradoxical. It seems as though they had set up, or had proposed to activate an archetypical ‘Fordist’ assembly line dealing in specific ‘types’ of output.

Though he recognised that his own interests were for the most part tied to the realm of praxis, the caretaker joined in with a passive examination of the collection - “the residue”. During this his mood changed as he surprisingly opened up to speak about the group’s identification with ‘the occult’ and a possible engagement with paranormal phenomena. He believed that the designs were “invoked through some process of automatism” but my conjecture about the energy generated by the group possibly being locked into the works was met with bemusement.

Ultimately, he could only admit to feeling ambivalent about our proposal to exhibit the collection. He finally commented that the works “might resonate, find a frequency …maybe even enter into dialogue with the dead artists also showing therein” but that he “personally thought they’d be better off left out in the street.”